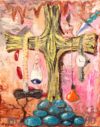

With Yes, Sir/Ma’am! No, Sir/Ma’am! Right Away, Sir/Ma’am!, Manuel Ocampo returns for his fourth solo exhibition at Tyler Rollins Fine Art, taking place from March 1 through April 14, 2018. The exhibition features large-scale paintings inspired in part by the work of Theodor de Bry (1528–1598), known for his detailed and sometimes fanciful engravings of the native inhabitants of the Americas and their recent contacts with European explorers and colonists. Ocampo intermixes scenes from these works with motifs taken from American political cartoons from the period of the Philippine American War (1899-1902), with their often outrageous ethnic stereotypes. That war is considered by many to be “America’s first Vietnam War,” and its years of invasions, insurgency, and atrocities remain a major touchstone in Philippine history, although they are largely forgotten in the US. Through the juxtaposition of imagery from two historical periods of contact and conflict between the Western and non-Western worlds, Ocampo explores the evolving role of visual representations in colonial expansion, both as complicit agents and as modes of resistance, while also reflecting on themes relating to personal identity, race, and migration that seem so relevant today. Ocampo’s new works were prepared in an open studio at the gallery, in which other artists were invited to collaborate. Based in New York, the Philippines, and Europe, they include: Daze, Jigger Cruz, Irene Iré, Lazaro Juan, Gorka Mohamed, Todd Richmond, Roger Kleier, Paolo Javier, and Jevijoe Vitug. A video of a performance by Paz Tanjuaquio is screened in a large cubic structure that evokes the balikbayan boxes used by Filipino overseas workers to send items back home.

Ocampo has been a vital presence on the international art scene for the past thirty years, with a reputation for fearlessly tackling the taboos and cherished icons of society and of the art world itself. Born in Metro Manila, the Philippines, in 1965, he moved to California in 1985, living first in Los Angeles from 1985-1994 and, after a few years in Spain, residing in San Francisco from 1999-2005. His first solo exhibition, which took place in LA in 1988, set the stage for a rapid rise to international prominence. By the early 1990s, his reputation was firmly established, with inclusion in Documenta IX (1992), and the Venice Biennale (1993). He was the youngest artist participating in Helter Skelter: L.A. Art in the 1990s at The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, in 1992, a seminal and at times controversial exhibition featuring artists such as Chris Burden, Mike Kelley, Paul McCarthy, Raymond Pettibon, Charles Ray, and Jim Shaw. Ocampo is considered a key figure in the Los Angeles art scene of that time, when he was noted for his bold use of a highly charged iconography that combined Catholic imagery with motifs associated with racial and political oppression. His paintings made powerful, often conflicted, statements about the vicissitudes of personal and group identities, and illustrated, sometimes quite graphically, the psychic wounds that cut deep into the body of contemporary society, translating the visceral force of Spanish Catholic art, with its bleeding Christs and tortured saints, into our postmodern, more secular era of doubt, uncertainty, and instability.

Ocampo moved back to the Philippines in 2005 and continues to be based primarily in Manila, where he has remained quite active in the local art scene, mentoring a generation of younger artists. In recent years, his works have featured more mysterious yet emotionally charged motifs that evoke an inner world of haunting visions and nightmares. He often makes use of an eclectic array of quasi-religious, highly idiosyncratic icons featuring teeth, fetuses, sausages, and body parts alongside more traditional Christian motifs. The process of artistic creation is often a central concern, with many works making ironic commentaries on notions of artistic inspiration, originality, and the anxiety of influence. The artist himself is frequently the subject of parody and self-mockery, sometimes appearing as a buzzard, a kind of cultural scavenger, or assuming slightly deranged alter egos. He frequently includes sly references to the works of other artists, just as in the past he often referred to the work of provincial painters of Catholic altars. His work was featured in the Philippine Pavilion in the 2017 Venice Biennale (see photo above), with a monumental installation of new paintings alongside three works from the mid-1990s.