Manuel Ocampo has been a vital presence on the international art scene for over twenty-five years, with a reputation for fearlessly tackling the taboos and cherished icons of society and of the art world itself. Now based in Manila, the Philippines, he had an extended residency in California in the late 1980s and early 1990s and continues to spend significant time working in both the US and Europe. Ocampo was featured in the Philippine Pavilion for the 2017 Venice Biennale, with a selection of paintings from the 1990s in dialogue with his recent work. The pavilion exhibition, entitled The Spectre of Comparison, was curated by Joselina Cruz, director of the Museum of Contemporary Art and Design, Manila, and also featured installation works by Lani Maestro. This marked Ocampo’s third showing in Venice following the 1993 and 2001 biennials.

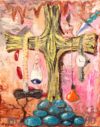

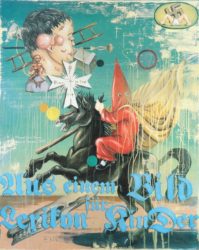

Ocampo’s first solo exhibition, which took place in Los Angeles in 1988, set the stage for a rapid rise to international prominence. By the early 1990s, his reputation was firmly established, with inclusion in Documenta IX (1992), the Venice Biennale (1993) and the seminal exhibition Helter Skelter: L.A. Art in the 1990s at The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (1992). During the ’90s, Ocampo was noted for his bold use of a highly charged iconography that combines Catholic imagery with motifs associated with racial and political oppression, creating works that make powerful, often conflicted, statements about the vicissitudes of personal and group identities. His works illustrate, often quite graphically, the psychic wounds that cut deep into the body of contemporary society. They translate the visceral force of Spanish Catholic art, with its bleeding Christs and tortured saints, into our postmodern, more secular era of doubt, uncertainty, and instability.

In recent years, Ocampo’s works have featured more mysterious yet emotionally charged motifs that evoke an inner world of haunting visions and nightmares. He often makes use of an eclectic array of quasi-religious, highly idiosyncratic icons featuring teeth, fetuses, sausages, and body parts alongside more traditional Christian motifs. The process of artistic creation is often a central concern, with many works making ironic commentaries on notions of artistic inspiration, originality, and the anxiety of influence. The artist himself is frequently the subject of parody and self-mockery; sometimes he appears as a buzzard, a kind of cultural scavenger, or assumes slightly deranged alter egos. He frequently includes sly references to the works of other artists, just as in the past he often referred to the work of provincial painters of Catholic altars. For The Corrections, his 2015 solo exhibition at Tyler Rollins Fine Art, Ocampo made silkscreens based on photographs of his older paintings, mainly well-known works from the ‘90s, altering the images to resemble darkened and distorted photographic negatives. New interventions were then hand painted on top of these images, creating rich, multi-layered compositions that capture a sense of the passing of time, the evolution of consciousness, and the ongoing structuring of personal and group identities.

Ocampo’s recent body of work, presented at Art Basel Miami Beach in 2017, took its inspiration from Helter Skelter on the 25th anniversary of that exhibition, reflecting on how its themes relating to personal identity, race, and migration seem so relevant today. The new works ground these issues in history, specifically the history of American colonialism in the Philippines. Ocampo appropriates motifs taken from an eclectic array of sources, ranging from Ad Reinhardt’s 1946 cartoon, How to Look at Modern Art in America, to American political cartoons from the period of the Philippine American War (1899-1902), with their often outrageous ethnic stereotypes. That war is considered by many to be “America’s first Vietnam War,” and its years of invasions, insurgency, and atrocities remain a major touchstone in Philippine history, although they are largely forgotten in the US. These recent works explore the role of visual representations in colonial expansion, both as complicit agents and as modes of resistance, while also pointing to the return to the fore of popular consciousness many identity issues that were so prominent in the 1980s.